FP SCOTUS Predictions: Supreme Court Will Rule Against Retired Firefighter in Post-Employment ADA Case

Insights

3.20.25

The Supreme Court will soon decide whether a retiree can sue a former employer under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) for discrimination in post-employment benefits. While the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals held that that such claims are not allowed under the ADA, federal appeals courts are divided over this issue, and SCOTUS will have the final say in resolving that split. If the Court rules in favor of the retiree, employers could face increased litigation from former employees with disabilities claiming discrimination in post-employment benefits – but we predict the Court will go the other way and affirm the 11th Circuit’s decision. Read on for an analysis of the issues and our specific predictions on how SCOTUS will decide the case.

What Happened?

Here’s the key background information on Stanley v. City of Sanford, Florida.

Factual Background

- Firefighter Retired After Becoming Disabled. Karyn Stanley served as a firefighter for the City of Sanford, Florida, for nearly 20 years before she took disability retirement in 2018 at the age of 47, two years after she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

- Two-Year Cap on Post-Employment Health Benefits for Disability Retirees. When Stanley had first joined the fire department in 1999, the city offered free health insurance until age 65 for certain employees who retired because of a qualifying disability. However, Stanley did not know the city changed that plan in 2003 to provide disability retirees only 24 months of free health insurance after retiring.

- Same Benefits Continued to Age 65 for Other Eligible Retirees. Under the City’s policy, all retirees, whether disabled or non-disabled, remained eligible to receive the health insurance subsidy until reaching age 65, so long as they had completed 25 years of service. Stanley had only completed 20 years of service before her disability forced her to retire, so she became responsible for her own health insurance premiums in December 2020, 24 months after her retirement date, when she was approximately 49 years old.

- Retiree Sued Former Employer. Stanley sued the City in 2020, claiming the reduction in benefits violated the ADA because it discriminated against her as a retiree with a disability. She sought to establish her entitlement to the long-term healthcare subsidy.

Legal Background

- ADA Anti-Discrimination Rule. Under Title I of the ADA, covered employers (employers with 15 or more employees, including state and local governments) are prohibited from discriminating against a “qualified individual” based on the individual’s disability in job application procedures, hiring, firing, advancement, compensation, job training, and “other terms, conditions, and privileges of employment."

- ADA Definition of “Qualified Individual.” The ADA defines a “qualified individual” as an individual who, with or without reasonable accommodation, “can perform the essential functions of the employment position that such individual holds or desires.”

- 11th Circuit Precedent. The appeals court ruled in 1996 (Gonzales v. Garner Food Services, Inc.) that the ADA prohibits discrimination only as to those qualified individuals who hold or desire to hold a job – barring a former employee from suing over discriminatory post-employment benefits. In Gonzales, the court distinguished Title I discrimination claims from Title VII’s anti-retaliation provision, which the court has held as allowing claims for post-employment retaliation because Title VII covers “employees” without any “temporal qualifier” and regularly uses that term to mean something more inclusive or different than current employees. This is noteworthy because Stanley argues that a post-Gonzales Supreme Court ruling (Robinson v. Shell Oil Co.), which adopted the same rule allowing post-employment retaliation claims under Title VII, undermines

Lower Court Rulings

- District Court. A Florida district court dismissed the Stanley case after concluding that Stanley could not state a plausible disability discrimination claim because the alleged discriminatory act – the health insurance subsidy ending 24 months after taking disability retirement rather than continuing to age 65 – occurred while she was no longer employed by the City.

- Appeals Court. The 11th Circuit agreed, reasoning that while the ADA protects against discrimination in fringe benefits, the law only gives employees and job applicants the right to sue, not retirees. The appeals court concluded that Stanley’s claim was barred by Gonzales, which it said remains good law is not implicated by Supreme Court’s holding in Robinson. The court, however, decided the case without considering Stanley’s newest argument – that she had actually suffered discrimination during her employment once disability retirement had become a foregone conclusion – because, the court said, Stanley had waited too long to make the argument.

- Circuit Split. The 11th Circuit’s position in Stanley aligns with the 6th, 7th, and 9th Circuits, but is at odds with the 2nd and 3rd Circuits, which have held that Title I’s anti-discrimination provision is ambiguous and resolved that ambiguity in favor of former employees.

What’s at Stake for Employers?

If the Supreme Court rules that Stanley can sue for discrimination under the ADA, employers nationwide would face greater exposure to disability discrimination claims from retirees and other former employees concerning post-employment benefits. Employers would then need to take even more caution when reducing or eliminating retirement or other post-employment benefits to ensure that the change does not disparately impact former employees with disabilities.

How Did the SCOTUS Oral Arguments Go?

The Supreme Court heard arguments on Jan. 13. In addition to each party’s counsel, the proceedings included an appearance from a U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) attorney who argued as a “friend of the court” in support of Stanley.

Disability Retiree’s Argument

The attorney for Stanley first argued that former employees may sue under the ADA when they allege that they were discriminated against as qualified individuals while they were still employed – the argument that the 11th Circuit had refused to consider, claiming it had been forfeited. Based on this narrow theory, Stanley’s counsel said, she has a right to challenge the alleged discriminatory policy, even if she was no longer employed at the time she brought suit, because she was subject to the policy during the two years she continued working following her Parkinson’s diagnosis, when she was indisputably a qualified individual. The DOJ attorney also argued in support of Stanley and agreed that this narrow rationale was the “most straightforward path” for the Court to rule in her favor.

Stanley’s counsel also asked the Court to consider adopting a broader rationale that would extend the ADA’s protections to former employees even if they could not point to any discriminatory act that occurred while they were still employed. He urged that post-employment benefits are “crucial to recruiting people to take on dangerous jobs like firefighting and policing,” and, in his rebuttal, argued that “the City’s extreme position creates perverse incentives for employers to hide discrimination until after retirement.”

Employer’s Argument

The attorney for the employer argued that Stanley cannot establish that the City discriminated against her while she was a qualified individual because the alleged discriminatory policy (the City’s 24-month limit on health insurance subsidies) applies only to disability retirees – individuals who, by definition, are permanently and completely unable to perform their jobs. Therefore, she argued, “the only time the alleged discrimination occurred was when she was an unqualified individual after she had taken her retirement.”

While the City’s counsel acknowledged that there could be a scenario where a qualified individual with a disability could be subjected to a discriminatory policy regarding post-employment benefits, she distinguished those hypothetical situations from the one in this case. “The difference,” she said, “is our policy is not no disabled person gets a pension. It’s a policy that applies only to people who become unable to do the job because they’re totally disabled.” She also framed the 24-month health insurance subsidy as “preferential” treatment for disabled retirees since it is available without the 25-years-of-service requirement that applies to non-disabled employees, rather than discriminatory treatment due to the 24-month cap that only applies to disabled retirees.

The Justices’ Responses

The Court expressed concerns over each party’s positions but overall seemed to lean more toward supporting Stanley. Justices Jackson and Kagan questioned how, under the City’s view, anyone could ever challenge disability discrimination in the context of retirement or post-employment benefits. Along the same lines, Justice Sotomayor expressed concern that without ADA protections, nothing would stop employers from discriminating against disability retirees.

Justice Alito, however, pressed Stanley’s counsel to explain how courts should approach the type of discrimination being alleged here: “How is a court supposed to determine whether this distinction between somebody who works 25 years and somebody who works a shorter period and retires based on disability is unlawful? What is that is the test for determining that?”

Meanwhile, Justice Thomas (and, at least initially, Justice Kagan) cast doubt over whether Stanley’s argument based on the narrow theory should be considered by SCOTUS at all, due to the murkiness over whether it had been properly raised in or addressed by the lower courts.

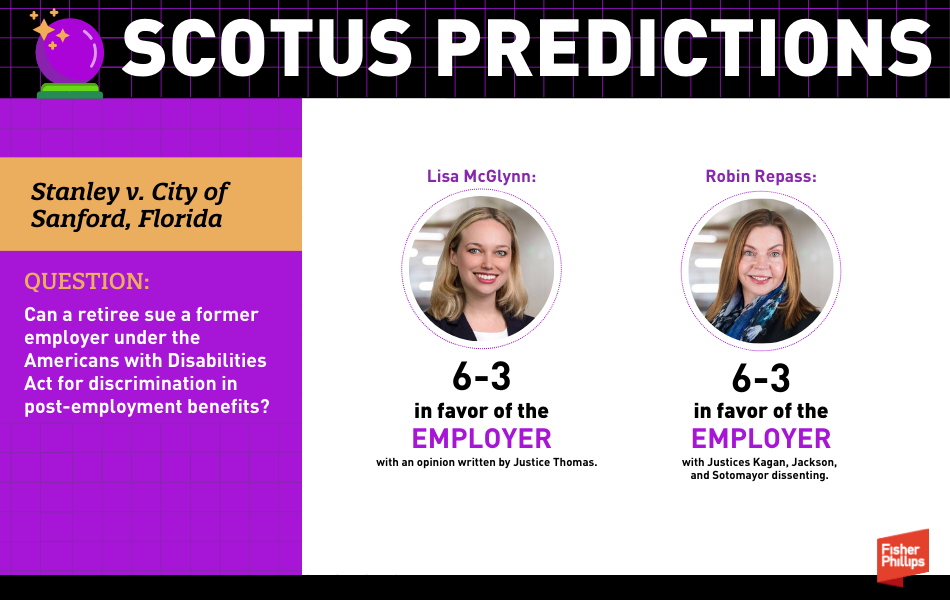

FP SCOTUS Prediction: Supreme Court Will Rule in Favor of the Employer

Both of us predict that the Court will affirm the lower court’s decision and hold that Stanley cannot maintain her claim under the ADA because she did not work for the city when her retirement benefits were terminated.

- Lisa McGlynn: The Court will issue a 6-3 decision in favor of the employer.While the Justices showed sympathy for Stanley, I believe the Court, with Justice Thomas writing for the majority, will ultimately side with the City of Sanford and find that the ADA does not entitle a former employee to sue for a denied benefit when that employee is no longer a “qualified individual.” Because a qualified individual is one who can perform the job he or she currently holds or desires, someone who is retired and no longer holding or seeking the job cannot be a qualified individual. Accordingly, I predict the Court will uphold the 11th Circuit’s ruling, which noted that Title I uses the present tense when defining “qualified individual” – indicating that the protections apply only to current or potential employees.

- Robin Repass: I agree with Lisa’s prediction. The Court will not accept Stanley’s invitation to take the “narrow path” by holding that she may maintain suit because she alleged discrimination while still employed by the City of Sanford. The Court is likely to find that doing so would construe the ADA too broadly and allow former employees to challenge post-employment discrimination. The vote will be 6-3 in in favor of the employer, with the following Justices agreeing with the City: Roberts, Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett. Justice Elena Kagan has signaled her interest in examining the narrower theory of whether Stanley could maintain suit because she alleged that she was discriminated against while still employed by the City, and will likely vote in favor of Stanley, as will Justices Jackson and Sotomayor.

Conclusion

We expect the court to issue an opinion sometime during the next few months. We will continue to monitor developments related to this case and provide an update when SCOTUS issues an opinion, so make sure you subscribe to Fisher Phillips’ Insight System to get the most up-to-date information. If you have questions, contact your Fisher Phillips attorney or the authors of this Insight.

Related People

-

- Lisa A. McGlynn

- Partner

-

- Robin Repass

- Partner